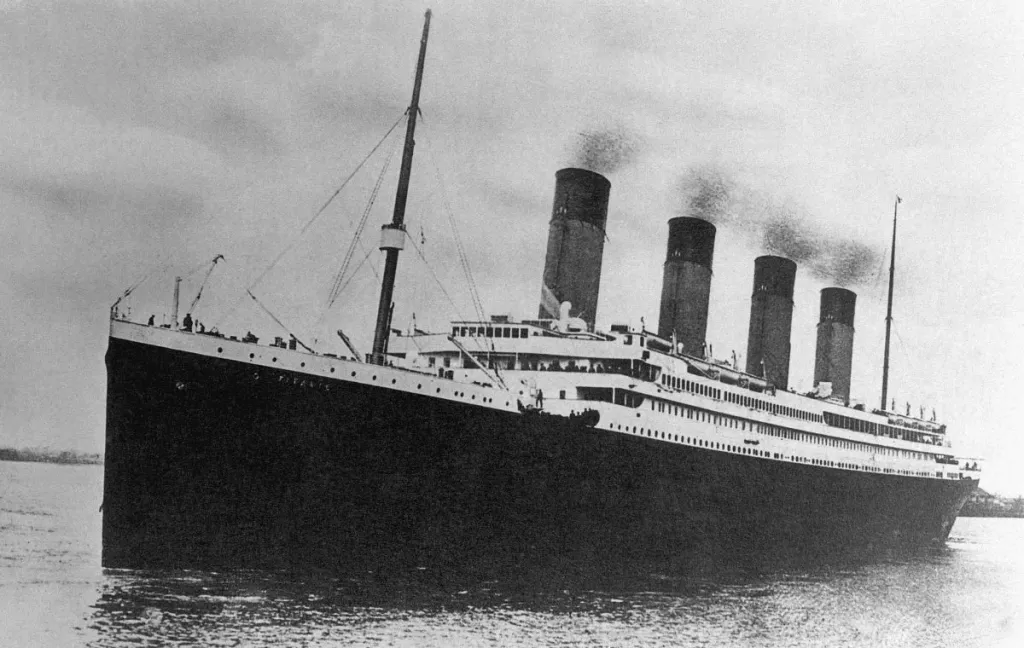

What do you know about the dogs on the Titanic? Over 100 years ago, one of the most tragic – and certainly, most famous – shipwrecks in history happened. Shortly before midnight on April 14, 1912, the R.M.S. Titanic struck an iceberg and sank into the Atlantic Ocean during the early hours of April 15. Over 1,500 people lost their lives.

The Titanic set sail on April 10, 1912 from Southampton, England. What many don’t know, however, is that when Titanic began its journey there were at least 12 dogs on board. All of the pups were accompanying first-class passengers on the voyage to New York. Of those 12, only 3 survived.

The three dogs who survived the Titanic

The first, Lady, a young Pomeranian, made it onto lifeboat #7 with her owner, Margaret Bechstein Hays. Hays wrapped Lady in a blanket as she boarded the lifeboat. This allegedly prompted another passenger to joke “Oh, I suppose we ought to put a life preserve on the little doggie, too.”

A second Pomeranian belonging to textile tycoon Martin Rothschild and his wife, Elizabeth Jane Anne, made it off of the Titanic. Elizabeth Jane Anne snuck the dog onto lifeboat #6. Sadly, Martin did not survive.

The last dog known to disembark the sinking Titanic belonged to publishing heir Henry S. Harper of Harper & Row and his wife, Myna. Sun Yat-Sen, a Pekingese, joined the Harpers and their interpreter on lifeboat #3.

What we know about the other dogs on the Titanic

Only a little is known about the dogs that lost their lives in the Titanic tragedy. A Fox Terrier and French Bulldog (named Gamin de Pycombe) are known to have passed.

Of the nine dogs that died, two belonged to William Ernest Carter, a leading coal industrialist from Philadelphia. Carter told his children, Lucy and Billy, that their Airedale Terrier and Cavalier King Charles Spaniel would be all right as the children boarded their lifeboat. Unfortunately, the dogs didn’t make it, and the family would later be compensated in an insurance settlement totaling $300.

One of the dogs that perished was the beloved Great Dane of first class passenger, Ann Elizabeth Isham. Isham begged the lifeboat captain to allow her to bring her dog on board, but her requests were denied because of the dog’s large size. Isham, distraught, refused to climb aboard the lifeboat, choosing instead to stay behind in the dog kennels with her best friend. Some reports suggest that a recovery vessel found Isham’s body days later, her frozen arms still grasping the dog she adored in a final hug.

J. Joseph Edgette is a professor at Widener University and curator of the university’s centennial Titanic exhibit. He was especially touched by the stories of the dogs onboard the ill-fated ship.

“There is such a special bond between people and their pets,” Edgette said in a press release in 2012. “For many, they are considered to be family members.”

“I don’t think any Titanic exhibit has examined that relationship and recognized those loyal family pets that also lost their lives on the cruise,” Edgette says.

Renewed interest in the Titanic has sparked another tragedy

In 2023, a private submersible — on an expedition to tour the wreckage of the Titanic — left five people missing and in need of rescue. Hailed as a chance to “become one of the few to see the Titanic with your own eyes,” by the Titanic submarine operator OceanGate Expeditions, the passengers were charged $250,000 to book their seat.

According to CNN, OceanGate Expeditions declined a voluntary safety review. This is despite employees raising concerns over “the vessel’s hull, including the thickness of the material used and testing procedures.” This is troubling because “[t]he 23,000-pound craft is made of highly engineered carbon fiber and titanium,” and employees are unsure if the submersible could withstand pressure at the depths it was expected to reach.

At the time of this writing, reports look bleak. According to Sky News, the Titanic submarine is most likely out of oxygen. “I’m afraid to say that even if we were to find Titan now, the time it would take to get down there, secure them, bring them up… it’s vanishingly small in terms of the likelihood of survival,” Retired rear admiral Chris Parry said.