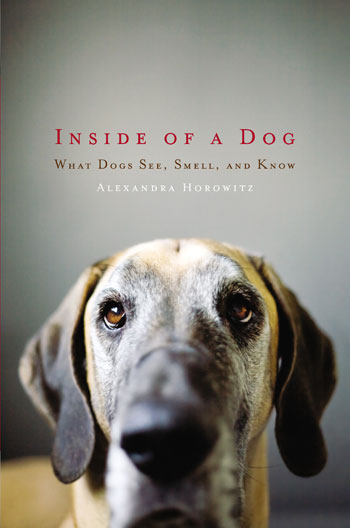

DogTime editor Leslie Smith interviews Alexandra Horowitz, author of the New York Times bestseller Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know

Despite its excellent reviews and months on the New York Times best-seller list, I wasn’t particularly excited to dig into Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know, the 2009 release by Alexandra Horowitz. I’d already consumed volumes on the topic of canine cognition and didn’t think this book could offer anything new or insightful.

I was wrong. Inside of a Dog is what you get when an extremely gifted writer and consummate dog lover decides to pursue science: Answers to questions you thought were unknowable, expressed in a most gratifying and accessible way. Inside of a Dog is the closest you may ever come to understanding what it’s like to be another species.

If you read all the best books about dogs, do not miss this one. And if you only ever read one book about dogs, read this one.

DogTime: Is there one simple thing we humans could do to improve our dogs’ lives or life with our dogs?

Alexandra Horowitz: The best science is all about close observation, and you can do that at home. The more we can put aside the ideas we have about what our dogs know, what they do, what they want, etc., and just watch them act, the better we’ll see what they are actually about. I sometimes tell people to try to forget everything they know about the dog, and pretend it is an alien animal arrived in their home: What is this alien doing?

For me, this was made easier by watching videos in slow, slow motion: I saw a lot that I never could have seen with the naked eye. Or set up a home video and watch what your dog does when you’re away. It is illuminating to see your dog act without you.

DT: Part of what makes Inside of a Dog so accessible and engaging are the interwoven observations of Pump and descriptions of your relationship. At home are you equal parts scientist and dog lover or does the scientist part of you drop into the background?

AH: I try to leave my scientist cap off when I’m dealing (now) with Finnegan or (earlier) Pumpernickel. That said, the cap has worked its way into my brain a bit and it is impossible to remove it entirely. I’m not sorry about that: the things that studying dogs and dog research have given me only contribute to my relationship with my dog.

I think some people worry that taking a scientific stance toward the dog risks de-romanticizing this special and somewhat mysterious relationship. I found exactly the opposite: thinking more about dogs let me look more closely at my own dogs, and really see what they were doing, which was more fascinating than I could have imagined.

One simple way that this informed my interaction with my dogs is the introduction of the “smell walk” (that I mention in my book). Knowing more about the terrific olfactory abilities of dogs prompts me to slow down on some of my walks, and indulge Finn in stopping to sniff wherever he wants. Sure, we might only make it three blocks in a half-hour, but he is enjoying it so much, it is time well spent.

DT: One of the most compelling ideas of the book is that dogs at some level do think about aspects their own lives, albeit not necessarily the exact same way humans do. Does this mean that dogs may actuallyreflecton their lives — or are they simply keeping track of where they buried a particular bone?

AH: Research hasn’t confirmed that dogs are “self-aware,” i.e., that they are thinking about their own life and themselves somewhat like we do. That said, it hasn’t (and can’t) confirm that they aren’t, either. One study I did, watching slow-motion video of dogs in social play, led me to the conclusion that dogs act as though they are thinking about the minds of other dogs. If so, this would be a kind of self-awareness.

And the example you mention, about where the bone is buried, is a telling one. Having a memory — and dogs’ memories are perfectly good — doesn’t mean that a dog sits back and reflects on the good old days the way we might. But it means that this information about their life informs their present, and their future, choices. That, at least, they share with us.

DT: You write that language “marks the difference” between human memory and dog memory. Is the same true of cognition — as Temple Grandin theorizes, do dogs think in pictures?

AH: There’s a popular notion that animals (and humans) either think “in pictures” or “in language.” While we might have the experience of thinking in one or the other (or both), there’s no evidence at all about what non-human animals think like. It might be in pictures, but who knows? I think we do them a disservice to imagine that if it’s not like us, it must be in this “simpler” way. Dogs are olfactory, more than visual: might they think in odor clouds?

DT: Were you surprised at the success of Inside of a Dog?

AH: Oh, sure, yes. I didn’t set out to write a best-selling book. I just wanted to write about the latest dog cognition research — much of which had never been discussed in popular books, because it is too recent. And I was really interested in using that research to address questions that I, as someone living with a dog, had about my dog. I think the idea of imaging the “dog’s point of view” had a lot of resonance with people.

DT: Our lack of understanding of the canine mind has led to some grim training techniques and disastrous co-habitation situations. What are the biggest misconceptions about dogs that still linger?

AH: The “pack” notion: that dogs live in a hierarchy and that we must be the leader, or else they will wrest leadership from us. Entirely untrue. Wolf packs are not like this, nor are dogs like this. Also the notion that dogs are just wolves in pretty clothing: a dog isn’t about to revert to being a wolf. And speaking of clothing, very few dogs need sweaters, raincoats, or booties.

I still get questions that imply that the person thinks that dogs understand everything we say, or else that dogs understand nothing at all. It’s funny how we sometimes treat them as either “just like us” or “entirely unlike us.”

DT: What are you currently working on and what’s next?

AH: I, and my fabulous students at my Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard College, are doing studies with dogs, testing anthropomorphisms that we make of dogs to see if they are correct. Right now we are doing a study to see if a dog has a sense of fairness — i.e., if he can find a situation “unfair.” If you and your dog are in NYC, we’d love to meet you! They are behavior studies, nothing harmful happens. It’s fun for dog and person alike.

I’m also writing a book that is not about dogs, per se. It is about walking in the city, though, and was prompted by thinking about how much walking with my dog in the city changed my perception of the city. I’ve taken walks with two dozen people whose expertise — from naturalist to architectural historian to artist — allows them to “see” things on the streets that I don’t notice. I’m aiming to enrich what we can notice on an ordinary walk.